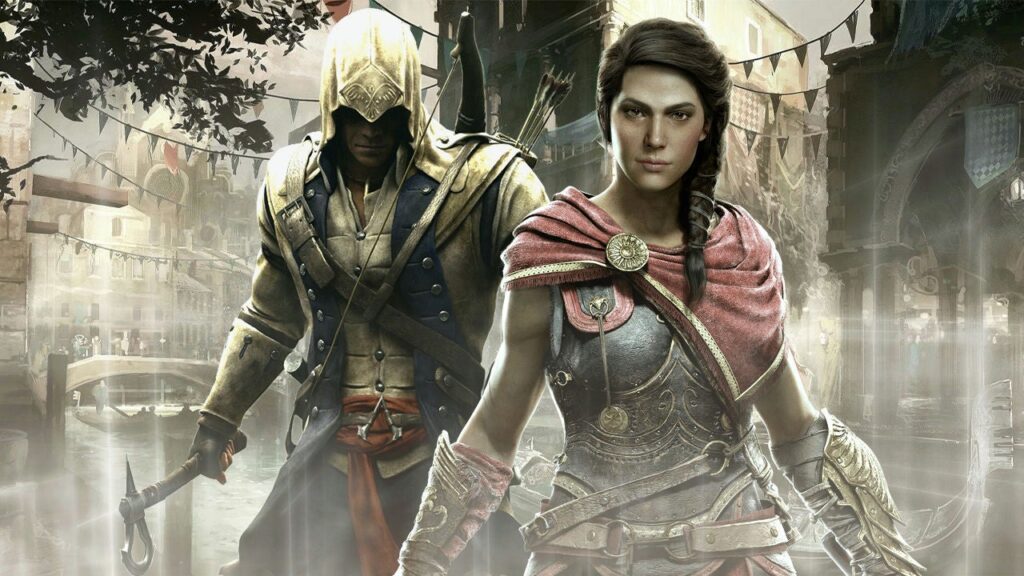

Why Assassin's Creed 2 and 3 have the best writing ever written in the series

Blog Andrew Joseph 15 Mar , 2025 0

One of the most memorable moments in the entire Assassin's Creed series takes place at the beginning of Assassin's Creed 3, when Haytham Kenway completes his end to the Assassin Band in New World. Or at least, the player is considered as an assassin. After all, Haytham used a hidden blade, as charismatic as the previous series protagonist Ezio Auditore, and until the campaign reached this point, he played the role of heroes, causing Native Americans to destroy and defeat the British Red from prison. It is only obvious when he utters the familiar phrase “The Father of Understanding Guides Us” that we have actually been following our swearing enemy, the Templar.

For me, this surprising setting represents the greatest awareness of Assassin's Creed's potential. The first game of the series introduces an interesting concept – find, understand and kill your target – but lacking in the story department, the protagonist Altaïr and his victims both completely lose their personality. Assassin's Creed 2 takes a step in the right direction by replacing Altaïr with the more iconic Ezio but fails to treat his opponent the same, and the big downside of its derivative Assassin's Creed is: the fraternity, Cesare Borgia, meets people who are particularly underdeveloped. Only in Assassin's Creed 3 set during the American Revolutionary War did Ubisoft's developer spend a lot of time running away from the hunter's hunter. It borrows an organic process from setup to reward, and therefore a delicate balance between gameplay and narrative has not been copied since.

While the current RPG era of the series has been well received by players and critics to a large extent, a large number of articles, YouTube videos, and forum posts agree that Assassin's Creed is falling and it's been a while. However, what exactly caused the debate. It points to some extent that the increasingly unrealistic modern gaming premises brings you against deities like Anubis and Fenrir. Others have implemented various romantic choices for Ubisoft, or, in the face of the much-picked situation of Assassin's Creed shadow, replaced its fictional protagonist to date with real-world historical figures, an African warrior called Yasuke. My personal nostalgia for gaming in the Xbox 360/PS3 era, and I don't think that's all. Instead, this decline is the result of the series’ gradual abandonment of character-driven storytelling, which is gradually buried in its vast sandbox.

Assassin's Creed has filled its original action-adventure formula with RPG and real-time service elements over the years, from conversation trees and XP-based flattening systems to loot boxes, Micrototransaction DLC, and gear customization. But the bigger the new staging has become, the emptiness they begin to feel, not just the myriad climbs, which are this-the-the-the-the-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-objection-tat-objection sixpions, and their basic storytelling.

While letting you choose what the character says or does should make the overall experience more immersive, in fact, I found it often has the opposite effect: as the script gets longer, many possible scenarios can be taken into account, but they feel they lack the same limited range of interactions as the game level. The series' collection of action-adventure eras, script-like scripts allow well-defined characters that are not cut off by the game's structure, requiring their protagonists to be on the whim of the player.

So while games like Assassin's Creed Odyssey have more content than Assassin's Creed 2, most of them feel wooden and knocked down. Unfortunately, this breaks the immersion. It's obvious that you're interacting with computer-generated characters, not complex historical figures. This contrasts with the franchise Xbox 360/PS3 era, which in my humble opinion produces some of the best writing in all games, the hot “Don’t follow me or anyone else!” addressed Haytham, the tragic island of Seliloqomic soliloqoo, after beating Savonarola, when he spoke when he was eventually killed by his son Connor:

“Don't think I'm intentionally touching your cheek and saying I'm wrong. I won't cry and wonder what will happen. I'm sure you understand. I'm somehow proud of you. You show great faith. Strength. Courage. All noble qualities. I should have killed you a long time ago.”

Writing has also suffered in other ways over the years. If modern games tend to stick to the dichotomy that Assassin is easy to digest = good and Templar = bad, then earlier games go out of their way to show that the line between the two orders is not as clear as it initially seems. In Assassin's Creed 3, everyone beats the Templars, using their last breath to make Connor – and expands the players – question their beliefs. William Johnson of negotiator said the Templar could have prevented Native American genocide. Hedonist Thomas Hickey called the assassin’s mission unrealistic and promised Connor would never be satisfied. Benjamin Church, who betrayed Haytham, declared it was “the whole perspective” and the British (from their perspective) saw themselves as victims, not invaders.

Haytham attempted to shake Connor's belief in George Washington, claiming that the country he would create would be no less than Americans trying to liberate their monarchy – when we discover that when we discover the order of Henchman's Henchman Charles Lee in Haytham, this order would be more real than burning down Connor's village. By the end of the game, players have more questions than answers, and the story is even more powerful.

Looking back at the series’ long history, that’s why a track from Assassin’s Creed 2 score “Ezio’s Family” resonates so much that it became the official theme of the series. PS3 games, especially Assassin's Creed 2 and Assassin's Creed 3, are their core character-driven experiences. The melancholy guitar strings of “Ezio’s Family” are not about evoking the game’s Renaissance environment, but Ezio’s personal trauma lost the family. While I appreciate the extensive world-building and graphic loyalty of the current generation of Assassin’s Creed games, I hope that this out-of-control franchise will one day shrink its scale and once again provide a focused, tailored story that will lead me into love initially. Sadly, in the huge sandbox and single player with live service ambitions, I worry that it is no longer a “good business.”

Tim Brinkhof is a freelance writer specializing in art and history. After studying journalism at NYU, he continued to write for Vox, Vulture, Slate, Polygon, GQ, Esquire and more.